- Fantomas!

- Come dite?

- Dico:

Fantomas!

- Cosa significa?

- Niente... e tutto!

- Ma che cos'è?

- Nessuno... ma qualcuno!

- Insomma, che cosa fa questo qualcuno?

- Fa paura!!!

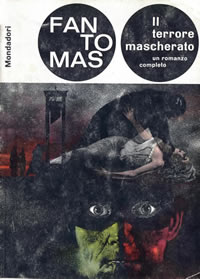

Così si apre il primo volume - Il terrore mascherato - della serie (bellissima, anche se non integrale) che Mondadori ha pubblicato fra il marzo 1963 ed il gennaio 1966.

E nelle poche righe introduttive:

"Fantomas c'est la mort", afferma senza falsa modestia l'interessato, e fin dal primo numero di questo nuovo mensile il lettore avrà modo di constatare che non è un'esagerazione.

Ancor oggi, a oltre cinquant’anni dalla sua prima apparizione, Fantomas conserva la sua fama di re del delitto, simbolo sinistro dell'astuzia criminale, minacciosa incarnazione del sangue freddo, della spietatezza, dell'inafferrabilità.

I circa quaranta romanzi di Allain e Souvestre che hanno per protagonista Fantomas - e che verranno qui pubblicati di mese in mese, ciascuno completo e in una nuova, accurata traduzione - costituiscono il più straordinario ciclo narrativo di tutta la letteratura poliziesca, e uno dei più grandi best-sellers di tutti i tempi.

Perché? Che cos'ha Fantomas di diverso, di più suggestivo, o memorabile, o impressionante? È forse più intelligente di Sherlock Holmes? È più agile di Arsenio Lupin? Più simpatico di Maigret? Più elegante di Philo Vance? Più vanitoso di Poirot? Che cosa lo distingue dagli altri leggendari eroi - buoni e cattivi - del poliziesco?

Una cosa sola, semplicissima e che tuttavia da al suo personaggio una enorme superiorità: Fantomas non ha volto.

A pagina 1 troviamo un ricco banchiere? Potrebbe essere Fantomas. A pagina 10 si presenta un mendicante zoppo? Chi ci dice che non sia Fantomas? A pagina 100 s'intrufola un apache? C'è caso che sia Fantomas. A pagina 200 incontriamo un cameriere calvo, un padre di famiglia, un medico, una cara vecchietta? Nulla vieta che si tratti in realtà di Fantomas.

Fantomas è tutti e nessuno, e un uomo capace di assumere qualsiasi identità finisce per essere in scena dal primo capitolo all'ultimo.

Juve il poliziotto, e Fandor il giornalista (ma anche loro, non saranno poi...?) che da un colpo di scena all'altro, da un capovolgimento a una rivelazione, da un grande albergo a una bettola, da una reggia a una cantina, gli danno affannosamente, vertiginosamente la caccia, hanno un solo modo per non sbagliare: sospettare di chiunque, non fidarsi di nessuno, mai.

Ai nostri lettori consigliamo di fare altrettanto. Prima di tutto perché si divertiranno di più; e poi perché, non conviene dimenticarlo, Fantomas c'est la mort. "

Questa breve introduzione non è firmata, ma con ogni probabilità è da attribuirsi a Carlo Fruttero (che i più conoscono in realtà soprattutto col cognome, abbinato a Lucentini: un po' come Garinei e Giovannini, Stanlio e Ollio, Starsky e Hutch...), che ha diretto e curato la collana. E infatti è Franco Lucentini l'ottimo (e libero) traduttore della deliziosa, inquietante Cantilena di Fantomas che apre il primo volume.

Fantomas-Fantômas è stato davvero uno dei fenomeni letterari "di genere" più interessanti del XX secolo, anche per l'insolito intreccio tra l'enorme successo di pubblico (in Francia della prima edizione Arthème Fayard 1911- 1913 vennero vendute oltre sei milioni di copie), e il consenso a volte entusiastico da parte dell'intellettualità: dai surrealisti ad Apollinaire, che definì l'opera "straordinaria, piena di vita e d´immaginazione, (...) dal punto di vista immaginativo una delle opere più ricche mai esistite." Consenso, oltre a tutto, che non si è esaurito nella tumultuosa stagione surrealista, ma, almeno in Francia, si è protratto a lungo: basti pensare a Magritte e a Queneau. Fantomas-Fantômas è stato davvero uno dei fenomeni letterari "di genere" più interessanti del XX secolo, anche per l'insolito intreccio tra l'enorme successo di pubblico (in Francia della prima edizione Arthème Fayard 1911- 1913 vennero vendute oltre sei milioni di copie), e il consenso a volte entusiastico da parte dell'intellettualità: dai surrealisti ad Apollinaire, che definì l'opera "straordinaria, piena di vita e d´immaginazione, (...) dal punto di vista immaginativo una delle opere più ricche mai esistite." Consenso, oltre a tutto, che non si è esaurito nella tumultuosa stagione surrealista, ma, almeno in Francia, si è protratto a lungo: basti pensare a Magritte e a Queneau.

Oggi, in realtà, se ne sono quasi perse la tracce (a maggior ragione, dunque, è particolarmente apprezzabile la raccolta di saggi pubblicata nel 2004: Fantômas. La vita plurale di un antieroe, a cura di Monica Dall'Asta, ed. Il principe costante), tanto che è stato ripubblicato solo il primo romanzo. Già la prima edizione Salani (1912-3), che pure ebbe notevole fortuna, e quelle successive, erano lentamente scomparse, e forse dobbiamo proprio all'acume e alla raffinatezza di Fruttero-Lucentini l'idea mondadoriana di far uscire nuovamente i 35 romanzi del primo ciclo (con le straordinarie copertine disegnate da Karel Thole).

Ai quali, comunque, non hanno fatto seguito altre significative iniziative editoriali. Nemmeno (ma questo forse è un bene) sull'onda del successo ottenuto dalla serie di pessimi (almeno dal punto di vista dell'impostazione "classica" dei personaggi) film di metà anni '60 interpretati dai peraltro bravissimi Louis de Funès e Jean Marais.

Mais Fantômas n'est pas mort...

|

Robin Walz and Elliott Smith

The first pulp fiction |

I romanzi Fantômas di Souvestre e Allain ci presentano un paradosso. Presentano un personaggio che commette crimini straordinariamente raccapriccianti senza apparente causa o motivazione, e che, alla fine di ogni romanzo, riesce a sfuggire alla punizione. Ma allo stesso tempo i romanzi erano immensamente popolari. Ogni libro della serie - e sono stati pubblicati al ritmo di uno al mese per 32 mesi consecutivi - è stato atteso con grande entusiasmo da un grande pubblico di lettori parigini di tutti i livelli sociali.

Naturalmente Fantômas potrebbe essere stato così popolare proprio perché i suoi crimini erano così orribili. È stata l'audacia delle sue imprese a renderle una lettura avvincente. Souvestre e Allain - e in seguito il regista Louis Feuillade - hanno fatto uso di ambientazioni parigine altamente riconoscibili per i crimini di Fantômas; le ambientazioni familiari hanno senza dubbio aumentato il brivido per i lettori. E l'improbabile fuga di Fantômas alla fine di ogni episodio ha solo stuzzicato la fame del pubblico per il prossimo.

La storia di come è stata prodotta la serie Fantômas è selvaggia come le trame dei romanzi stessi, e come una rete di plausibilità e miti. Pierre Souvestre era un avvocato fallito che si era rivolto al giornalismo automobilistico; Marcel Allain, dieci anni più giovane di lui, ha fatto domanda per la posizione di segretario di Souvestre e ha ottenuto il lavoro producendo un lungo articolo sul posto su un nuovo camion che non aveva mai visto. Presto i due lavoravano per una varietà di riviste, generando copie che includevano serial polizieschi ambientati nel mondo delle corse automobilistiche (per L'Auto) o del teatro (per Comoedia, una recensione teatrale).

I loro romanzi serializzati li hanno portati all'attenzione di Arthème Fayard, l'editore di romanzi tascabili economici nella sua serie Le Livre Populaire ("libro popolare").

La maggior parte dei libri della serie erano ristampe di romanzi del XIX secolo (in modo che Fayard potesse evitare di pagare i reali), con copertine a colori dall'illustratore di casa Gino Starace, stampati nel modo più economico possibile e venduti al prezzo incredibilmente basso di 65 centesimi - una somma alla portata di tutti tranne che ai parigini più poveri. Era un'idea brillante, che decenni dopo sarebbe stata adattata dagli editori americani per creare un intero genere, pulp fiction. Fayard ha assunto Souvestre e Allain per scrivere una serie di fantastici romanzi. Come Allain ricordò in seguito, durante la corsa in metropolitana per firmare il contratto i due autori hanno inventato il nome "Fantômus". A quanto pare Fayard ha letto male il titolo, e gli autori non si sono mai preoccupati di correggerlo; così è nato Fantômas.

Il loro contratto richiedeva che Souvestre e Allain producessero un romanzo integrale ogni mese. Per sfornare così tanta verbosità, gli autori hanno prodotto i romanzi in modo da assembly. Nella prima settimana hanno delineato la trama di base, plagiando spudoratamente dai loro precedenti serial e dalle storie poliziesche di altri scrittori.

I furti dalle storie di Maurice Leblanc (il "gentile ladro" Arsène Lupin), Emile Gaboriau (l'ispettore della sicurezza Monsieur Lecoq) e Gaston LeRoux (il giornalista investigativo Rouletabille) sono particolarmente evidenti. Nelle due settimane successive Souvestre e Allain hanno dettato la loro parte della storia alle loro segretarie, e Allain ha trasmesso i punti principali della trama a Gino Starace, che ha disegnato una copertina adeguatamente lurida. Nell'ultima settimana si sono scambiati copie, hanno scritto paragrafi di transizione per entrare e uscire dai capitoli dell'altro e l'hanno inviato a Fayard. Hanno continuato a questo livello di produzione letteraria per 32 mesi consecutivi!

Le trame sognate da Souvestre e Allain erano sorprendenti, con molteplici travestimenti (compresi quelli cross-gender), incoerenze di tempo e spazio, gadget spettacolari e infinite atrocità violente. E, a differenza dei loro predecessori del XIX secolo, i romanzi di Fantômas non si concludono con il ripristino dell'ordine morale. Invece, l'arcicriminale fugge, per perpetrare altre crudeltà nel prossimo episodio.

In questi elementi i surrealisti avrebbero in seguito visto parallelismi con la loro preoccupazione per il meraviglioso; per saperne di più sul fascino del surrealista per i romanzi e i film di Feuillade, vedi l'articolo di Robin Walz "Serial Killings: Fantômas, Feuillade, and the Mass-Culture Geneology of Surrealism".

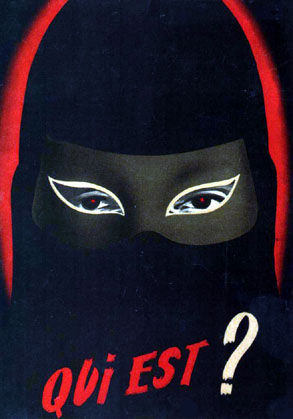

Il primo romanzo della serie apparve nel febbraio 1911 e fu un successo immediato, aiutato dalla campagna pubblicitaria con l'immagine indimenticabile di un uomo gigante mascherato che stringe un pugnale che incombe sul cuore di Parigi (vedi I romanzi di Fantômas). Alla fine Fayard avrebbe pubblicato più di 5 milioni di romanzi di Fantômas (di gran lunga la serie più popolare all'interno di Le Livre Populaire). L'immensa popolarità dei romanzi scatenò una guerra di offerte tra i due principali studi cinematografici francesi; Gaumont vinse e cinque film di Fantômas diretti da Louis Feuillade furono prodotti nel 1913 e nel 1914. I film sono stati anche un enorme successo popolare, e anche se Souvestre e Allain avevano apparentemente ucciso sia Juve che Fantômas nella puntata finale La Fin De Fantômas, è possibile che sarebbero stati prodotti più romanzi o più film. Tuttavia, pochi mesi dopo l'uscita del quinto film di Fantômas, la Francia fu immersa nella prima guerra mondiale e Feuillade era andato a combattere nelle trincee.

Entro la fine della guerra, Souvestre era morto (dell'epidemia di influenza spagnola). Feuillade, ferito all'inizio della guerra, riprese il cinema elaborando gli elementi e l'atmosfera dei film di Fantômas nel suo capolavoro Les Vampires e in altri serial, ma non fece mai un altro film di Fantômas.

Allain avrebbe continuato a sposare la vedova di Souvestre e nel corso dei decenni avrebbe scritto tre nuove serie di avventure di Fantômas da solo. E dopo Fantômas di Feuillade, un serial muto americano di 20 episodi, seguivano 6 lungometraggi sul suono francese e una serie TV di quattro episodi. Ma nessuna delle manifestazioni successive del Genio del Crimine raggiunse né la popolarità né il successo artistico (involontario) delle sue incarnazioni originali.

ns. traduzione da http://www.fantomas-lives.com/ |